It’s an accusation that can be thrown at any organisation, and any employee network, at any time. But at Radius, we get asked how to avoid “virtue signalling” during Pride Month more than any other. So what about those rainbow logos and marches, and just what is the problem with virtue signalling anyway?

First of all, it’s a lazy term.

As the Cambridge Dictionary would have it, it’s “an attempt to show other people that you are a good person, for example by expressing opinions that will be acceptable to them, especially on social media. Virtue signalling is the popular modern habit of indicating that one has virtue merely by expressing disgust or favour for certain political ideas or cultural happenings.”

But when people talk about virtue signalling, it usually means one of two things. Used without context, it’s never clear whether it’s a legitimate criticism of someone who is all talk and no walk, or whether it’s a lazy shutdown of someone with good intentions. There doesn’t seem to be much nuance to this conversation starter…

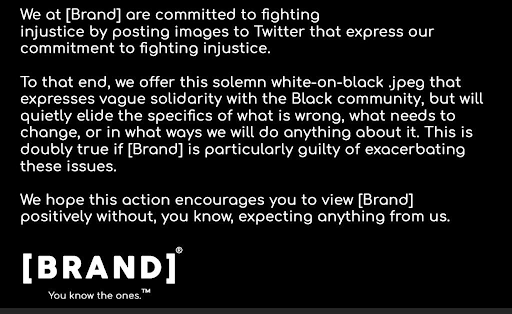

But it goes beyond the individual to organisations, as illustrated by this meme we were sent about 100 times throughout June 2020 concerning empty statements on Black Lives Matter.

It’s also what the LGBT+ groups would call rainbow-washing, or environmental groups call green-washing, and every network has their equivalent.

The origins of this “washing” go all the way back to the 16th century in the UK. It was literally a cheap white paint made of chalked lime that was used to wash walls and other surfaces to give a quick freshened look. Think “Changing Rooms” circa 1591 but with a bigger budget.

Hop over the water to 1800 United States, and The Philadelphia Aurora advises “if you do not whitewash President Adams speedily, the Democrats, like swarms of flies, will bespatter him all over, and make you both as speckled as a dirty wall, and as black as the devil.” Whitewashing at the Whitehouse? Never! Bonus fact: the Whitehouse used to be grey, and was only washed white with lime in 1798, so it’s no wonder the metaphor caught on.

It was then variously used across many nations and political persuasions as a way to describe covering up scandals. It’s also been used since the 20th century to describe the specific erasure of black people from history.

The first Earth Day was in 1970, and it’s estimated that public utilities in the US spent eight times more on advertising their green credentials as they did on pollution reduction. But it wasn’t until 1986 that Jay Westerveld used the term “greenwashing” in an essay, detailing how hotels promoted reusing towels to “save the environment”, while putting little or no effort into reducing their waste. He concluded that the real objective was profit by saving on laundry costs, and not an environmentally conscious act.

“Greenwashing” inspired the term “pinkwashing” in 2010, and was first used to specifically criticise “homonationalism” in Israel. This refers to the process of selectively agreeing with sexual minorities, and exploiting them, in order to justify racism, xenophobia, and persecution of the poor (in other words, the intersection of gay identity and nationalism). Although this term was popularised by Jewish American writer Sarah Shulman, many LGBT+ Israelis object to the term.

In many places ‘pinkwashing’ has been replaced by “rainbow-washing”, that old accusation that companies will change their logo to a pride flag during June, but do little else to support or represent LGBT+ people the rest of the year.

Almost every identity and cause can find their own version of “washing”, but as you can see, the interpretations of what it means can be a little… murky… and in need of a good scrub.

So, how do we spot virtue signalling in a way that is useful and specific?

1. Are they telling the whole truth?

For example, a cosmetics company is free to state that their products are “cruelty-free” or “not tested on animals” as long they don’t do it themselves. However, they may be constructing their product with chemicals supplied by other companies who have done just that. Always be aware when a “badge” is only indicating a narrow set of circumstances.

2. Where’s the proof?

Is it easy to access the information that proves this claim, or are they asking for trust. 87% of people said I am awesome. They were all from my family though, so to be honest, I’m a bit peeved about that missing 13%. Is the claim independently verified by a third party? And who owns that “third party”? Did they pay for that recognition?

3. Sorry, what?

Look out for claims that are so poorly defined or broad that its real meaning is likely to be misunderstood by the consumer. “All-natural”, for example, isn’t necessarily good for you. Arsenic and lead are pretty natural, but let’s not stick them in a salad.

4. Juxtaposition

Good film editors know you can imply anything with the right juxtaposition of images. Seeing someone smiling in one shot, then the next is a giggling baby is a lovely short film. Seeing someone smiling, followed by a bloody corpse is… well, what Hitchcock preferred. This also happens with virtue signalling where companies can give the false impression of endorsement where none exists, purely through proximity.

5. Sleight of hand

You know when those slightly annoying street magicians attack you with a card trick, and they are waving one arm around wildly so that you don’t see what the other hand is doing? That. Companies may make a claim that is truthful, but irrelevant to the information you are trying to seek (like if I put my address in your app, it’s great that you won’t send me mail, but will you send a street magician round?)

Finally, and we’re not going to give this a number because it stands by itself, but… are they just lying?

ARE THEY???

We wouldn’t encourage you to use the term virtue signalling within your internal conversations, precisely because of the ambiguity of how this can be interpreted. But it’s certainly worth keeping an eye on your social media for accusations of such. Because when it comes to “virtue signalling”, it could be that some people don’t agree with the virtuous sentiment at all. But for most employee networks, they recognise this all too well as a lack of specific action. The critique of an organisation’s character in this instance is best handled by clearly communicating WHAT you’re doing, not just your sentiments.

As ever, it always comes back to strategy. Be specific about your gaps and your actions, then nobody can accuse you of blurring the truth.

We all want to promote equality and eliminate bias. And sometimes, even with success, this story can be lost in a world of generic EDI efforts, rather than relate specifically to your organisation – for example, better reporting of gender pay-gaps, or more accessible working practices, which could and should relate to any company.

So to supercharge your efforts in the battle against virtue signalling, look to demonstrate the unique ways in which your brand as an organisation and a network have made an impact, which relates specifically to the product or service that you offer.

We’ll explore those examples another time, but for now, we’d love to hear your examples, and hopefully, include them in our future articles.